![]() Número 25, enero, 2025:

62–69

Número 25, enero, 2025:

62–69

ISSN versión impresa: 2071–9841 ISSN versión en línea: 2079–0139 https://doi.org/10.33800/nc.vi25.370

Nota científica

UNUSUAL PRESENCE OF ATLANTIC SHARPNOSE SHARK

(RHIZOPRIONODON TERRAENOVAE) NEONATES IN A COASTAL LAGOON IN SOUTHEAST GULF OF MEXICO

Presencia inusual de neonatos de cazón de ley (Rhizoprionodon terranovae) en una laguna costera del sudeste del golfo de México

Armando T. Wakida-Kusunoki1, Vicente Anislado-Tolentino2*

& Luis Fernando Del Moral-Flores3

1Centro Regional de Investigación Acuicola y Pesquera Yucaltepén, Instituto Mexicano de Investigación en Pesca y Acuacultura Sustentable (IMIPAS). Boulevard del Pescador s/n esquina Antigua Carretera a Chelem Yucalpetén, Yucatán, 97320, México. armandowakida@yahoo.com.mx, < https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7917-2651

2Grupo de Investigadores Libres Sphyrna (GILS) Boulevard del Cimatario 439, Constelación, Querétaro, 76087, México.

3Facultad de Estudios Profesionales Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Avenida de los Barrios

Número 1, Colonia Los Reyes Ixtacala. Tlalnepantla, Estado de México, 54090. México. delmoralfer@gmail.com, < https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7804-2716

*Corresponding author: anislado@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2184-0047

[Received: September 28, 2024. Accepted: November 22, 2024]

ABSTRACT

This study reports for the first time the presence of Rhizoprionodon terraneovae neonates in a coastal lagoon in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico. The observations suggest the presence of neonates was due to the salinity values being similar to those of the coastal zone (32 ppt) and that they may have been attracted by the high presence of penaeid shrimp. The presence of this species in this lagoon supports the knowledge of the biology and ecology of the species, which will contribute to its proper fishing management.

Keywords: Carcharhinidae, sharpnose shark, coastal lagoon, Yucatan, Celestún.

RESUMEN

Este estudio reporta por primera vez la presencia de neonatos de Rhizoprionodon terraneovae en una laguna costera en el sureste del golfo de México. Las observaciones sugieren que la presencia de neonatos se debió a que los valores de salinidad eran similares a los de la zona costera (32 ppt) y que pudieron haber sido atraídos por la alta presencia de camarones peneidos. La presencia de esta especie en esta laguna apoya el conocimiento de la biología y ecología de la especie, lo que contribuirá a su adecuado manejo pesquero.

Keywords: Carcharhinidae, Cazón de ley, laguna costera, Yucatán, Celestún.

The Atlantic sharpnose shark (Rhizoprionodon terraenovae) is a small carcharhinid shark that inhabits the western Atlantic Ocean, from New Brunswick, Canada to the Gulf of Mexico and Honduras (Ebert et al., 2021), and is the most abundant shark species in catches in the Mexican coastal waters of the Gulf of Mexico (DOF, 2022). It has slow growth, late sexual maturity, high fecundity, and early life mortality (Simpendorfer, 1999). In the southern Gulf of Mexico, neonates are abundant in May (Márquez-Farias & Castillo-Geniz, 1998). Parsons & Hoffmayer (2005) found that the neonates appear in spring in shallow water when the temperature of the water is 20 to 22 °C and move out in autumn when the temperature of the water is 24 to 26 °C, coinciding with the depleting oxygen level.

In addition to being found in coastal waters, Rhizoprionodon terraenovae has been found in US estuaries and coastal lagoons (Castro, 1993), where it depends on tides and water temperature (Swift & Portnoy, 2020). It is reported that immediately after hatching they can disperse within estuaries, where distribution and relative abundance of R. terraenovae are conditioned by environmental factors, such as temperature and dissolved oxygen (Parsons & Hoffmayer, 2005), as well as the characteristic behavior of the species, which does not make large movements, preferring to stay in the same region (Carlson & Beremore, 2003; Carlson et al., 2008). According to Suarez-Moo et al. (2013), in the Gulf of Mexico, R. terraenovae can overcome all geographic barriers, resulting in a single population in this region, and it is likely that newborns and juveniles enter estuaries and coastal lagoons, as they do in the USA. On the other hand, Carlson et al. (2008) found that young-of-the-year (YOY) juveniles leave and enter bays and inlets when waters are warm, however they do not mention whether this shark enters as far as the middle of estuaries. Ward-Paige et al. (2014) for Florida, and Bangley et al. (2018) for North Carolina show that Atlantic sharpnose sharks only stay in the vicinity of inlets of lagoon systems. Castro (2011) mentions that hatchlings and juveniles are abundant in coastal and estuarine waters during the summer, although he does not mention how far into estuaries they venture. For Mexico, there is only one report of the presence of a juvenile in the inland waters of the Tecolutla River and the Tuxpan River estuary, Veracruz (Castro-Aguirre et al., 1999).

The Celestún lagoon is an epikarst estuary; in springs the ground water flows from rainfall percolate quickly, the lagoon salinity increasing from a minimum 14 ppt in the north lagoon to 33 in the southern lagoon close to the ocean (Hardage et al., 2022). The lagoon is divided into three regions: seaward, with salinity of 33–38 ppt; middle, with salinity of 22–32 ppt; and inner, with salinity of 11–20 ppt, with the highest values in the dry season from March to May (Herrera-Silvera & Ramírez-Ramírez, 1998). The freshwater inputs are in the inner region, the Celestún bridge is in the middle region, where the mixohaline water condition (salinity 10 to 30 ppt) depends on the tides (Valdés et al., 1988). A recent increase in salinity suggests lower precipitation and possible drought conditions (Hardage et al., 2022), however the effects of modifications in groundwater flows derived from anthropocentric activities must be considered (Villalobos, 2004). The records of ichthyofauna entering the Celestún lagoon do not include any shark species (Arceo-Carranza et al., 2010; Vega-Cendejas, 2004).

On May 18, 2022, at 22:00 hours, one male and one female individual of R. terraenovae were captured by rod fishing with an 8/0 hook and dead shrimp as bait, and on May 20, 2022, at 22:15 hours, three more females were captured using an artisanal shrimp fishing gear called a triangle (Wakida-Kusunoki et al., 2016; Wakida-Kusunoki & Rojas-González, 2021).

The capture of the specimens was carried out on the access bridge to Celestún, Yucatan, approximately 60 m from the western shore of the lagoon (20°51’28.8” N, 90°22’55.2” W, Fig. 1). Depth was taken with a lead line, salinity with an Atago Master ® refractometer and temperature with a submergible thermometer with a scale from -10 to 50 °C.

Figure 1. Celestún lagoon map. Dot shows the sample site. Maps by Vicente Anislado-Tolentino.

The specimens were identified according to the taxonomic key described by Castro (2011), Compagno (1984), and Grace (2001), and morphometric measurements were taken using an ichthyometer and a calliper (0.01 mm). Basic statistical values [arithmetic mean (Average) and standard deviation (SD)], of the morphometric measurements expressed as percentages of the total length were estimated.

The specimens were fixed in formaldehyde (10 %), preserved in ethyl alcohol (70 %), and deposited in the Ichthyological Collection of the Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala (CIFI), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, under code number CIFI-2009.

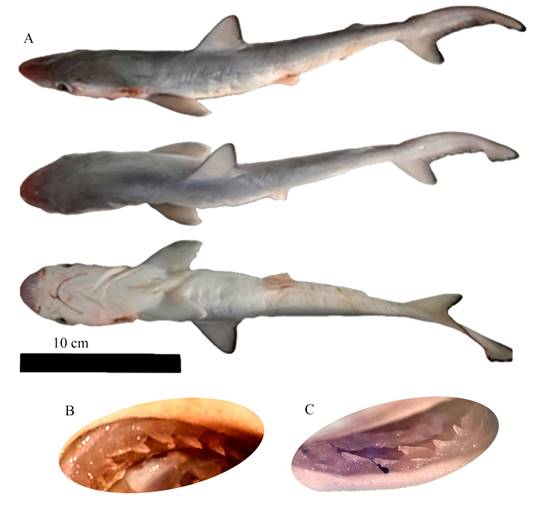

The environmental parameters recorded in the capture area were depth (2.5 m), salinity (32 ppt) and water temperature (28 °C). Five specimens caught were between 302–350 mm total length (TL) and 89.6–121 g total weight (Table I). The individuals were identified by having fairly large eyes, average long upper labial furrows 2.3% TL (0.2 SD), average pre-narial length

4.5 % TL (0.2 SD), 13 hyomandibular pores, first dorsal fin origin slightly in front of pectoral fin, free rear tips, second dorsal fin origin over anal fin, mid base inserts, pectoral fins with white margins, dorsal fin tips dusky. Upper teeth with finely serrated oblique cusps (Fig. 2). All individuals had a healthy but observable umbilical insertion.

Table I. Basic statistical values of the morphometric measurements of Rhizoprionodon terraenovae neonates caught in the middle region of the Celestún lagoon, Mexico. Average is the arithmetical mean, SD is the standard deviation, n = 5.

|

Measurements |

Average (min-max) |

|

Total weight (g) |

102 (89.6–121) |

|

Total length (mm) |

323 (302–350) |

|

Measurements as % of total length |

|

|

Furcal length |

80.5 (79.9–81.5) |

|

Pre-caudal length |

74.2 (73–76.7) |

|

Pre-second dorsal fin length |

61.8 (61.3–62.2) |

|

Pre-first dorsal fin length |

31.8 (31.7–32) |

|

Head length |

23.6 (22.6–24.5) |

|

Pre-branchial length |

19.6 (19.1–20.5) |

|

Pre-orbital length |

8.2 (7.6–8.9) |

|

Pre-narial length |

4.5 (4.3–5) |

|

Pre-oral length |

8.6 (8.3–8.9) |

|

Eye length |

2.7 (2.5–2.9) |

|

Eye height |

2.6 (2.3–2.8) |

|

Mouth length |

7.2 (6.7–7.9) |

|

Mouth width |

7.2 (6.8–7.9) |

|

Lower labial-furrow length |

1.5 (1.4–1.7) |

|

Upper labial-furrow length |

2.3 (2–2.5) |

|

Pectoral-fin inner margin |

8.4 (8.3–8.6) |

|

Pelvic-fin inner margin |

2.5 (2.3–2.6) |

|

Subterminal caudal margin |

3.0 (2.8–3.4) |

|

First gill slit height |

2.6 (2.6–2.7) |

|

Preventral caudal margin |

12.2 (11.6–12.6) |

|

Prenarial length |

4.0 (3.6–4.4) |

|

Lower postventral caudal margin |

10.0 (9.8–10.4) |

|

Internarial width |

6.2 (6.0–6.4) |

|

Dorsal caudal margin |

23.2 (22.–23.8) |

|

Pectoral-fin pelvic-fin space |

18.1 (18.0–18.2) |

|

Pelvic-fin posterior margin |

2.3 (2.2–2.4) |

|

Hyomandibular pores |

13 |

Figure 2. Rhizoprionodon terraenovae. A, male specimen of 328 mm total length, caught in the middle region of Celestún lagoon, Mexico. B, upper tooth left side and C, lower tooth right side. Photo A by Armando T. Wakida-Kusunoki, photo B and C by Luis Fernando Del Moral-Flores.

According to the length (302–350 mm TL) of the captured specimens and the umbilical insertion, these corresponded to neonates. This coincides with the birth lengths of R. terraenovae reported in the coastal zone of Campeche of 300 to 382 mm (Márquez-Farias & Castillo-Geniz, 1998; Martínez-Cruz et al., 2016). On the other hand, the middle region of Celestún is highly productive, with richness of decapods (shrimp and crabs) and small fishes (Arceo-Carranza et al., 2010; Wakida-Kusunoki & Rojas-González, 2021). In the southern part of the Gulf of Mexico, R. terranovae has been shown to prey on these groups, and their availability with respect to high salinity and sea surface temperature is correlated with dietary changes in R. terranovae (Viana-Morayta et al., 2020), and therefore may influence the spatial food segregation of neonates.

Despite the great effort to study its fish fauna, there are no previous reports of the presence of this species in the Celestún and coastal lagoons of the Yucatan peninsula (Caballero-Vázquez et al., 2005; Ordoñez-López & García-Hernández, 2005; Palacios-Sánchez et al., 2015; VegaCendejas, 2004). From the reports of Márquez-Farias & Castillo-Geniz (1998), who found an abundance of hatchlings in May along the coast of Campeche, it has been assumed that R. terranovae is a common inhabitant of the coastal lagoons of the southeast Gulf of Mexico. However, as demonstrated by Wiley & Simpfendorfer (2007) for the Everglades National Park, the Atlantic sharpnose shark is a rare inhabitant of estuaries, hence in the case of the Celestún lagoon it has not been reported until this occasion where it was captured in a local fishery but with intense fishing effort.

This report of the presence of this species in the lagoon is new for the zone and supports the knowledge of the biology and ecology of the species, and will contribute to its proper fishing management policies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank IMIPAS for its financial support for the research project “Evaluation of the effect of unrecorded shrimp capture in Celestún,” as well as monitoring of invasive species to evaluate their effect on shrimp populations, which were used for sampling, from which the analyzed samples were obtained. To SNII-SECIHTI for their support during this study.

REFERENCES

Arceo-Carranza, D., Vega-Cendejas, M E., Montero-Muñoz, J. L. & Hernández de Santillana, M. J. (2010). Influencia del hábitat en las asociaciones nictimerales de peces en una laguna costera tropical. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 81, 823–837. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2010.003.652

Bangley, C. W., Paramore, L., Dedman, S. & Rulifson, R. A. (2018). Delineation and mapping of coastal shark habitat within a shallow lagoonal estuary. PLoS ONE, 13(4), e0195221. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195221

Caballero-Vázquez, J. A., Gamboa-Pérez, H. C. & Schmitter-Soto, J. J. (2005). Composition and spatio-temporal variation of the fish community in the Chacmochuch Lagoon system, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Hidrobiológica, 15(2 Special), 25–225.

Carlson, J. K. & Baremore, I. E. (2003). Changes in biological parameters of Atlantic sharpnose shark Rhizoprionodon terraenovae in the Gulf of Mexico: evidence for densitydependent growth and maturity?. Marine and Freshwater Research, 54(3), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF02153

Carlson, J. K., Heupel, M. R., Bethea, D. M. & Hollensead, L. D. (2008). Coastal habitat use and residency of juvenile Atlantic sharpnose sharks (Rhizoprionodon terraenovae). Estuaries and Coasts, 31, 931–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-008-9075-2

Castro, J. I. (1993). The shark nursery of Bulls Bay, South Carolina, with a review of the shark nurseries of the southeastern coast of the United States. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 38(1–3), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00842902

Castro, J. I. (2011). The sharks of North America. Oxford, EE:UU: University Press.

Castro-Aguirre, J. L., Espinosa-Pérez, H. & Schmitter-Soto, J. J. (1999). Ictiofauna estuarinolagunar y vicaria de México. Mexico City, Mexico: LIMUSA, Instituto Politécnico Nacional.

Compagno, L. J. V. (1984). FAO Species catalogue. Vol. 4. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Part 2. Carcharhiniformes. FAO Fisheries Synopses, 125, 478–481.

DOF. Diario Oficial de la Federación. (2022). Acuerdo por el que se da a conocer el Plan de Manejo Pesquero de Tiburones y Rayas del Golfo de México y Mar Caribe. Jueves 9 de junio de 2022. https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5654592&fecha=09/06/2022# gsc.tab=0

Ebert, D. A., Dando, M. & Fowler, S. (2021). Sharks of the world, a complete guide. Princeton EE:UU.: Princeton University Press.

Grace, M. (2001). Field guide to requiem sharks (Elasmobranchiomorphi: Carcharhinidae) of the Western North Atlantic. NOAA technical report NMFS 153. https://repository.library. noaa.gov/view/noaa/3197

Hardage, K., Street, J., Herrera-Silveira, J. A., Orbele, F. K. J. & Paytanet, A. (2022). Late Holocene environmental change in Celestun Lagoon, Yucatan, Mexico. Journal of Paleolimnology, 67, 131–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-021-00227-4

Herrera-Silvera, A. & Ramírez-Ramírez, J. (1998). Salinity and nutrients in the coastal lagoons of Yucatan, México. Verhandlungen des Internationalen Verein Limnologie, 26, 1473–1478.

Márquez-Farias, J. F. & Castillo-Geniz, J. L. (1998). Fishery biology and demography of the Atlantic sharpnose shark, Rhizoprionodon terraenovae, in the southern Gulf of Mexico. Fisheries Research, 39, 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-7836(98)00182-9

Martínez-Cruz, L. E., Zea-de la Cruz, H., Oviedo-Pérez, J. L., Morales-Parra, L. G. & Balan-Che, L. I. (2016). Aspectos Biológicos pesqueros del cazón tutzún Rhizoprionodon terraenovae, en las costas de Campeche, México. Ciencia Pesquera, 24 (Special), 23–35.

Ordoñez-López, U. & García-Hernández, V. D. (2005). Ictiofauna juvenil asociada a Thalassia testudinum en Laguna Yalahau, Quintana Roo. Hidrobiológica, 15 (2 Special), 195–204.

Palacios-Sánchez, S., Vega-Cendejas, M. & Hernández, M. (2015). Ichthyological survey on the Yucatan coastal corridor (Southern Gulf of Mexico). Revista Biodiversidad Neotropical, 5(2), 145–551 https://doi.org/10.18636/bioneotropical.v5i2.167

Parson, G. R. & Hoffmayer, E. R. (2005). Seasonal changes in the distribution and relative abundance of the Atlantic sharpnose shark Rhizoprionodon terraenovae in the North Central Gulf of Mexico. Copeia, 4, 913–919. https://doi.org/10.1643/0045-8511(2005)005[0914:SCITDA]2.0.CO;2

Simpendorfer, C. A. (1999). Mortality estimates and demographic analysis for the Australian sharpnose shark, Rhizoprionodon taylori from northern Australia. Fishery Bulletin, 97, 978–986.

Suárez-Moo, P., Rocha-Olivares, A., Zapata-Perez, O., Quiroz-Moreno, A. & Teyer, L. F. S. (2013). High genetic connectivity in the Atlantic sharpnose shark, Rhizoprionodon terraenovae, from the southeast Gulf of Mexico inferred from AFLP fingerprinting. Fisheries Research, 147, 338–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2013.0.003

Swift, D. G. & Portnoy, D. S. (2020). Identification and delineation of essential habitat for elasmobranchs in estuaries on the Texas coast. Estuaries and Coasts, 44(3), 788–800. https://doi.org/:10.1007/s12237-020-00797-y

Valdés, D. S., Trejo, J. & Real, E. (1988). Estudio hidrológico de la Laguna Celestún, Yucatán, México, durante 1985. Ciencias Marinas, 14(2), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.7773/cm.v14i2.591

Vega-Cendejas, M. E. (2004). Ictiofauna de la Reserva de la Biosfera Celestún, Yucatán: una contribución al conocimiento de su biodiversidad. Anales del Instituto de Biología de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 75(1), 193–206.

Viana-Morayta, J. E., Torres-Rojas, Y. E. & Camalich-Carpizo, J. (2020). Diet shifts of Rhizoprionodon terraenovae from the southern Gulf of Mexico: possible scenario by temperature changes. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research, 48(3), 406–420.

https://doi.org/10.3856/vol48-issue3-fulltext-2433

Villalobos, Z. G. J. (2004). Reservas de la biosfera costeras: los Petenes y Ría Celestún. Capítulo 27 Casos de Estudio. In A. E. Rivera, G. J. Villalobos, A. I. Azuz, M. F. Rosado (Eds.), El manejo costero en México (pp. 397–412). Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, SEMARNAT, CETYS-Universidad, Universidad de Quintana Roo.

Wakida-Kusunoki, A. T. & Rojas-González, R. I. (2021). First amphibian report in artisanal shrimp fisheries bycatch: unusual presence of Gulf Coast Toad Incilius valliceps (Anura: Bufonidae). Herpetology Notes, 14, 1463–1465.

Wakida-Kusunoki, A. T., Rojas-González, R. I., Toro-Ramírez, A., Medina-Quijano, H. A., Cruz-Sánchez, J. L., Santana-Moreno, L. D. & Carrillo-Nolasco, I. (2016). Caracterización de la pesca de camarón en la zona costera de Campeche y Yucatán. Ciencia Pesquera, 24(1), 3–13.

Ward-Paige, C. A., Britten, J. L., Bethea, D. M. & Carlson, J. K. (2014). Characterizing and predicting essential habitat features for juvenile coastal sharks. Marine Ecology, 36(1), 419–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/maec.12151

Wiley, T. R. & Simpfendorfer, C. A. (2007). The ecology of elasmobranchs occurring in the Everglades National Park, Florida: implications for conservation and management. Bulletin of Marine Science, 80(1), 171–189.

Citation: Wakida-Kusunoki, A. T., Anislado-Tolentino, V. & Del Moral-Flores, L. F. (2025). Unusual presence of atlantic sharpnose shark (Rhizoprionodon terraenovae) neonates in a coastal lagoon in southeast Gulf of Mexico. Novitates Caribaea, (25), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.33800/nc.vi25.370