INTRODUCTION

The extant genus Tropidophis (Bibron in Cocteau & Bibron, 1843) includes 32 known species (Uetz et al., 2020) distributed throughout the Caribbean and South American continent. Most of its diversity is concentrated in the Greater Antilles and Bahamas islands (Hedges, 2002), with only five species occurring on the continent (Curcio et al., 2012; Uetz et al., 2020). With 16 species currently described, Cuba contains 53 % of the genus diversity, including its type species, T. melanurus (Schlegel, 1837), and some of the oldest named species [e.g.: T. pardalis (Gundlach, 1840) and T. maculatus (Bibron in Cocteau & Bibron, 1843)]. Up to six species occur sympatrically at a few localities (Hedges, 2002), representing the largest assemblage of these snakes throughout the distribution of the genus (e.g., four species at Soroa, Western Cuba: T. maculatus, T. melanurus, T. pardalis, and T. feicki). Ecological partitioning is suggested by the existence of terrestrial and arboreal species with distinct morphological trends (Hedges & Garrido, 1992). Only a few species are widely distributed and relatively common (e.g., T. melanurus and T. pardalis) with most being geographically restricted or rare.

Among the 16 Cuban species of Tropidophis, 11 are classified in the highest categories of threats, following IUCN criteria (González et al., 2012). However, only two species (Tropidophis hardyi and T. hendersoni) seem to be outside regions covered by the Cuban National System of Protected Areas (SNAP), thus deserving special attention by local authorities (Rodríguez-Schettino et al., 2015).

Stull (1928), Schwartz and Marsh (1960), and Hedges (2002) provided the broadest systematic reviews of Cuban species of Tropidophis. Apart from these revisionary accounts, most contributions are papers describing new species or subspecies (e.g.: Bailey, 1937; Schwartz, 1957; Schwartz & Thomas, 1960; Schwartz & Garrido, 1975; Hedges & Garrido, 1992, 2002; Hedges et al., 1999, 2001; Domínguez et al., 2006), complementary morphological data and/or new geographic records (Rehak, 1987; Fong, 2002; Domínguez & Moreno, 2005, 2006 abc; Domínguez et al., 2005; Domínguez & Parada, 2009; Fong & Armas, 2011; Torres et al., 2013b; Díaz et al., 2014, Torres & Martínez-Muñoz, 2014; Iturriaga & Olcha, 2015; Cajigas et al., 2018; Torres et al., 2018), descriptive synopses of the generic fauna and/or comprehensive distribution maps (Schwartz & Henderson, 1991; Tolson & Henderson, 1993; Rodríguez-Schettino et al., 2013; García-Padrón et al., 2020), natural history updates (Henderson & Powell, 2009; Polo & Arango, 2011; Fong et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2013a; Iturriaga, 2014; Díaz et al., 2014; Torres et al., 2014, 2016, 2018; Armas & Iturriaga, 2017; Rodríguez-Cabrera et al., 2017, 2020 ab; Torres & Rodríguez-Cabrera, 2020) or repetitions of previously published information (eg: Torres et al., 2017).

In the latest review of the genus, Hedges (2002) grouped species within a new taxonomic scheme (five groups). This author mentioned that a phylogenetic analysis based on DNA sequences supported his classification along with morphological characters. However, the referred phylogeny was never published. Other phylogenetic studies based on genetic sequences (Wilcox et al., 2002; Reynolds et al., 2014, 2018) included one or very few Cuban Tropidophis within a broader context not intended to define species interrelationships. Recently, a number of new generic and subgeneric names splitting the genus Tropidophis were given by Hoser (2013) without any support of scientific evidences. Kaiser et al. (2013) discussed the many reasons for rejecting this and other taxonomic papers published by Hoser. Ultimately, a large consortium of herpetologists requested that the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) invalidate the new names from this source, as his practice was considered unethical and potentially harmful for taxonomic stability (Rhodin et al., 2015). Therefore, we refrain from using these names, which ultimately are not compatible with the results presented herein.

OBJECTIVES

To describe a new species of Tropidophis from the eastern region of Cuba based on morphological and genetic evidence.

To discuss and update the phylogenetic relationships of the Cuban Tropidophis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

External morphology. We examined a total of 103 specimens of 16 Cuban Tropidophis (listed in Appendix 1) from the following institutions (abbreviations in parentheses): American Museum of Natural History, New York (AMNH); herpetological collection BIOECO, Museo de Historia Natural Tomás Romay, Santiago de Cuba (BSC.H); private collection of Michel Sánchez Torres (CMST); Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, La Habana (CZACC); collection of the Institute of Biology deposited at the Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, La Habana (IB); Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Boston (MCZ); Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Cuba, La Habana (MNHNCu); National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. (USNM); Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, Ann Harbor (UMMZ).

Scale counts, measurements, color pattern characterization, and general terminology essentially follow Schwartz and Marsh (1960: 51–52). Measurements were taken with a digital caliper (0.01 mm accuracy) and a ruler was used to measure snout-vent length (SVL). A dissecting microscope (Swift M27LED) was used for morphological examination and scale counts. Head length was measured from the tip of snout to the angle of the jaw. Snout length was taken from the tip of snout to the anterior border of eye. Head width (HW) was defined as the distance at the widest point of the temporal area. Eye diameter (ED) was measured horizontally. Neck width (NW) was measured posterior to the occiput. Dorsal scale rows were counted behind the head, around midbody, and anterior to the vent; the values are respectively reported as a formula (eg: 20–23–19). To facilitate counting, a thin entomological pin was used as a landmark every 10 ventral scales. Supralabial and infralabial scales were both counted on the left and right sides (l/r) from behind the rostral or mental scale, respectively, to the mouth commissure (again a land mark was made by using an entomological pin). Color designations follow the color catalogue for field biologists by Köhler (2012).

DNA extraction, processing and molecular phylogeny. The molecular phylogenetic analysis covers most species of Cuban Tropidophis, except for T. nigriventris for which no samples were available at the moment. Genetic samples were obtained from the liver of each specimen and stored in 100% ethanol. The protocols for DNA extraction and amplification are basically the same as those used by Figueroa et al. (2016). Two regions of mitochondrial DNA [12S rRNA, and Cytochrome b] and 1 nuclear gene (brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF), total of 1495 bp., were amplified using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Primers were synthesized from Adalsteinsson et al. (2009): 12S (5’-AAACTGGGATTAGATACCCCACTAT-3’; 5’-CGTAACATGGTAAGCGTACTGGAAAGTG-3’);BDNF(5’-GACCATCCTTTTCCT KACTATGGTTATTTCATACTT-3’;5’-CTATCTTCCCCTTTTAATGGTCAGTGTACAAAC-3’), and from Pook et al. (2000): Cyt-b (5’-TCAAACATCTCAACCTGATGAAA-3’; 5’-GGCAAATAGGAAGTATCATTCTG-3’). Tropidophis haetianus (T. haetianus Species Group, sensu Hedges, 2002) was included as outgroup in the analysis. The sequences for this species were available in Gen Bank (accession numbers AY988039; FJ755181).

Phylogenetic relationships were estimated using maximum likelihood (ML). The appropriate model of sequence evolution and model parameters were estimated using MODELTEST (Posada & Crandall, 1998). ML estimation was performed with Treefinder (Jobb et al., 2004) and their robustness was validated through a bootstrap analysis of 1000 replications.

ZooBank nomenclatural act. LSID urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:28DA59CC-8987-4740-A6465A6CB5038720. According to current Cuban regulations for genetic information our sequences were unable to be uploaded into Gen Bank. Tissue samples and corresponding voucher specimens are specified and can be studied following the terms set by Cuban authorities.

Tropidophis steinleini, sp. nov.

Figures 1 and 2 (A–C): external morphology; Figure 3: molecular phylogeny; Figure 4: distribution map; Figure 5: habitat.

Holotype. MNHNCu 5079 an adult female collected in the surroundings of the lighthouse of Maisí, Guantánamo Province (20°14’32.0”N; 74°08’36.9”W), by Luis M. Díaz and Antonio Cádiz on October 31 of 2014.

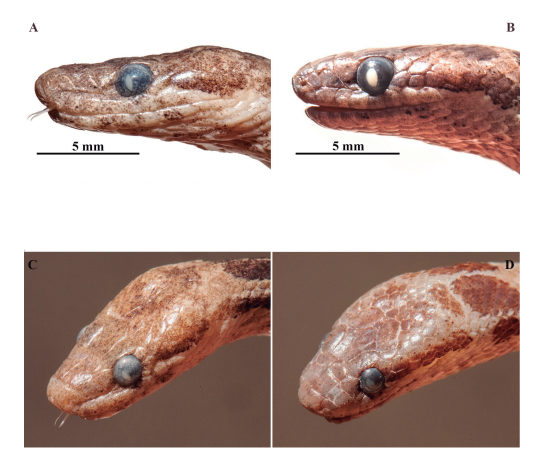

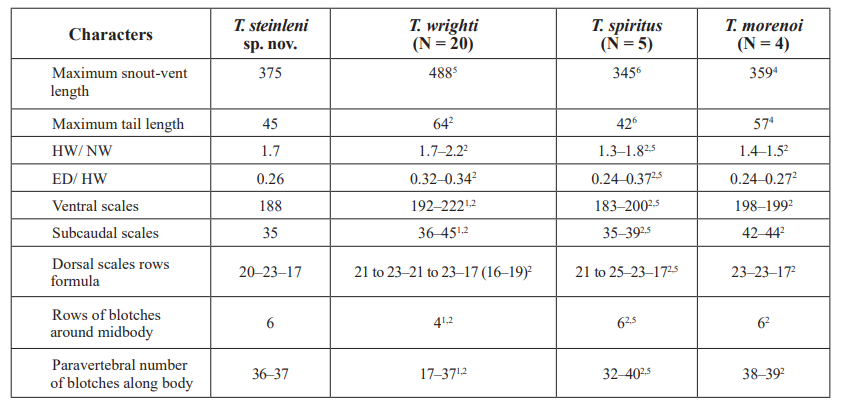

Diagnosis. Species in the Tropidophis pardalis species group as defined in the herein-presented molecular phylogeny (see Fig. 3, also Fig. 6 for species comparisons, and the Discussion). Body slender and laterally compressed; head distinctive from neck; 6 rows of dark blotches around body; some of the paravertebral and lateral blotches are longitudinally fused; 23 scale rows around midbody; 188 ventral scales; an evident groove above the supralabial scales; first supralabial slightly higher than second. Regarding morphology and the phylogenetic relationships, the new species is most similar to T. spiritus, T. morenoi and T. wrighti (Table I; Fig. 6 F, G, H, respectively). In the three species the first supralabial scale is much lower than second one; the head is gradually tapered in profile compared with the flat head top and a higher snout of the new species; a groove over the supralabial scales is absent (Fig. 2). T. wrighti has four rows of large blotches around body instead of 6, contrasting on a homogenous gray to white-colored background (Fig. 6H); some of the blotches are fused at the mid-dorsum but not in a distinctive longitudinal way; ventral scale counts (192–222) are higher than in Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov. T. morenoi and T. spiritus have 183–200 ventral scales, widely overlapping with Tropidophis steinleni sp. nov., and similar coloration considering that the three species have 6 rows of blotches around the midbody and pale lower flanks; however, the head shape is different (Fig. 2) as mentioned above. The snout is slightly shorter in available T. spiritus and T. morenoi (30–33 % of head length, x = 31 %, n = 7) compared with Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov. (34 %); paravertebral blotches are not longitudinally enlarged in T. spiritus and T. morenoi (Fig. 6 F, G), but instead some transversal fusion may exist, giving them a banded appearance (a condition not present in the new species); head is darker in T. spiritus and T. morenoi, with more evident and contrasting pattern of blotches and stripes which is somewhat diffuse or barely evident in Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov.

Diagnosis (Español). Especie del grupo Tropidophis pardalis, como lo define la filogenia presentada (Fig. 3, también véase la Fig. 6 para una comparación entre las especies, y la Discusión). Cuerpo estilizado y lateralmente comprimido; cabeza diferenciada del cuello; 6 hileras de lunares alrededor del cuerpo; algunos de los lunares dispuestos en posición lateral y paravertebral se hallan fusionados longitudinalmente; 23 hileras de escamas alrededor de la mitad del cuerpo; 188 escamas ventrales; un surco evidente por encima de las escamas supralabiales; primera escama supralabial ligeramente más alta que la segunda. Atendiendo a la morfología y relaciones filogenéticas, la nueva especie requiere una comparación más precisa con T. spiritus, T. morenoi y T. wrighti (Tabla I; Fig. 6 F, G, H, respectivamente). En estas tres especies la primera escama supralabial es notablemente más baja que la segunda; vista lateralmente, la cabeza se arquea gradualmente a diferencia del perfil recto y el hocico elevado de la nueva especie; el surco sobre las escamas supralabiales está ausente (Fig. 2). T. wrighti tiene 4 hileras de grandes lunares alrededor del cuerpo en vez de 6, los cuales contrastan sobre un fondo entre gris y blanco (Fig. 6H); algunos lunares se fusionan en el centro del dorso, pero no longitudinalmente; el conteo de escamas ventrales (192–222) es más alto que en Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov. T. spiritus y T. morenoi tienen las escamas ventrales en el rango 183–200, lo cual se superpone con Tropidophis steinleni sp. nov., y también presentan una coloración similar si se tiene en cuenta que en ambas especies existen 6 hileras de lunares alrededor de la mitad del cuerpo y que la parte baja de los flancos es distintivamente más pálida; sin embargo, la forma de la cabeza es diferente (Fig. 2) como ya se ha mencionado anteriormente; el hocico es ligeramente más corto en los especímenes disponibles de T. spiritus (30–33 % del largo de la cabeza, x = 31 %, n = 7) en comparación con Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov.

(34 %); los lunares paravertebrales no se fusionan longitudinalmente en T. spiritus y T. morenoi

(Fig. 6 F, G), sino transversalmente de manera que puede existir la apariencia de bandas (una condición ausente en la especie nueva); la cabeza es más oscura en T. spiritus and T. morenoi, con patrones de manchas y franjas contrastantes, los cuales resultan difusos y menos evidentes en Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov.

Figure 1. Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov., two different views of the female holotype MNHNCu 5079 in life. Photos: L. M. Díaz.

Description of holotype. Snout-vent length: 375 mm; tail: 45 mm; head length: 12.6 mm; snout length: 4.3; head width: 7.6 mm; eye diameter: 2.0 mm; eyes moderately protruded; neck width: 4.3 mm; supralabials: 10/9; infralabials: 11/11; dorsal scales formula: 20–23–17; subcaudal scales: 35; all scales are smooth; parietal scales narrowly separated; one preocular scale; 3 postoculars; nasals divided; blotches along tail: 6/6.

Color in life. Overall coloration in tones of brown, reddish-brown, tan and cream; dark blotches very conspicuous over the much paler interstitial areas. Color slightly changes with metachrosis. Description following color references by Köhler (2012): Dorsal dark blotches Maroon

(color 39) to Warm Sepia (color 40). Blotches surrounded by a distinctively paler ring of Chamois (color 84). Interstitial areas among blotches are a combination of Cinnamon-Rufous (color 31) and Brick Red (color 36). Ventral coloration starts on lower flanks and is Cream White (color 52). Blotches on ventral surface same color like dorsal ones or Prout´s Brown (color 47). Head dorsally with a combination of Cinnamon (color 21) and Kingfisher Rufous (color 28); barely patterned. Eyes Drab (color 19), with paler borders of Cinnamon Drab (color 50), and a weak central band of Natal Brown (color 49). A nuchal area of similar coloration than eye.

Table I. Morphological comparisons among three related species of Cuban snakes of the genus Tropidophis

Measurements are in millimeters (mm). Comparative data are from Schwartz and Henderson (1992) 1, Hedges (2002)2, Domínguez et al. (2005)3, Domínguez and Moreno (2006a)4, Fong and Armas (2011)5, and specimen CZACC 56606(see Appendix I).

Color in ethanol (after four years of preservation). Specimen drab-gray, with horn-white lower flanks and belly; blotches are dark brown almost black; postocular stripe paler than pattern on the side of neck; another diffusely evident stripe irradiate diagonally from the lower margin of eye to posterior supralabial scales and continued on corresponding infralabials; posterior part of head with a somewhat rhomboidal and slightly evident dark pattern; an interocular bar is barely defined.

Figure 2. Head shape in two species of the genus Tropidophis. A and C, Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov., holotype; B and D, T. spiritus. A and B, profile of the head showing its relatively flat upper surface and the high snout of T. steinleini (A) compared to the gradually tapered head (B) of T. spiritus (CZACC 4.5660). C and D, dorsolateral view of the head showing the supralabial groove of T. steinleini (C) versus the gradually convex side of the snout in T. spiritus. Photos: L. M. Díaz.

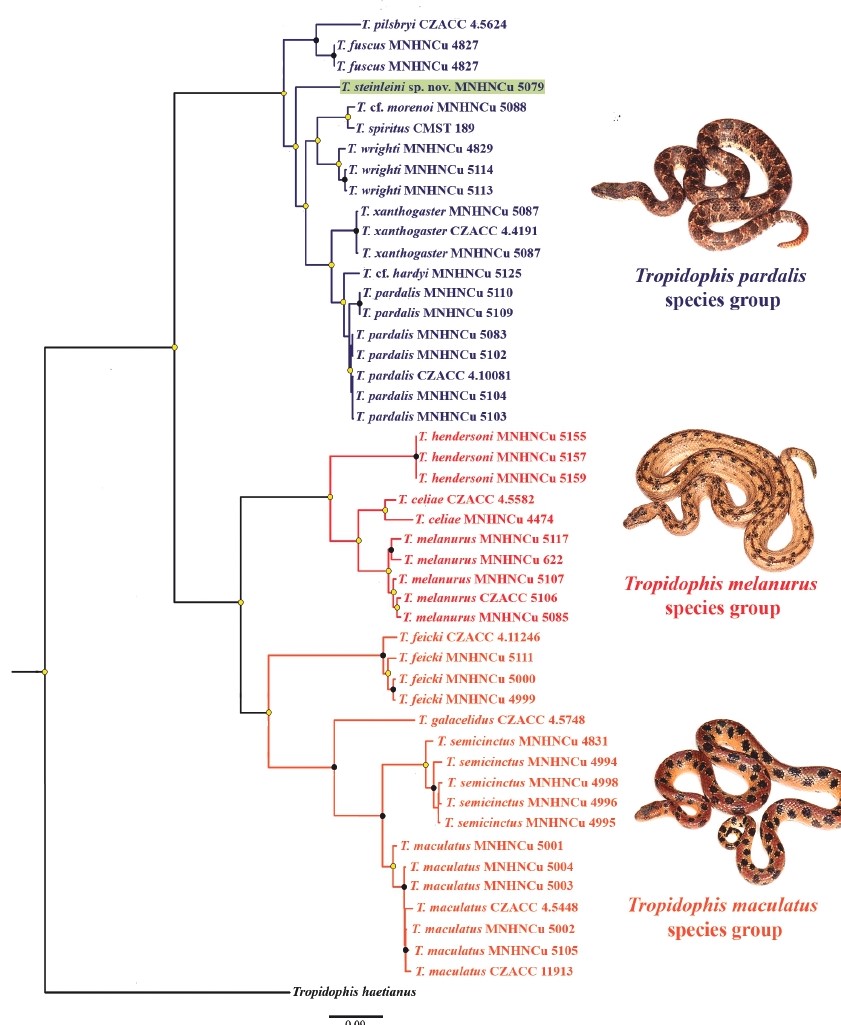

Figure 3. Maximum likelihood phylogeny of sampled snakes of the genus Tropidophis based in two mitochondrial and one nuclear gene, showing the three major Cuban clades and the position of Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov. The nominal, representative species of each group: T. pardalis, T. melanurus and T. maculatus, are respectively illustrated. Voucher’s catalog numbers are listed in Appendix 1. Tree is rooted with T. haetianus (from Hispaniola). Black circles: bootstrap = 100; yellow circle: bootstrap 81–99; no circle: bootstrap ≤ 80. Photos by L. M. Díaz.

Etymology. The species is named with gratitude, after our German colleague Claus Steinlein, for his support of the authors’ herpetological research in Cuba.

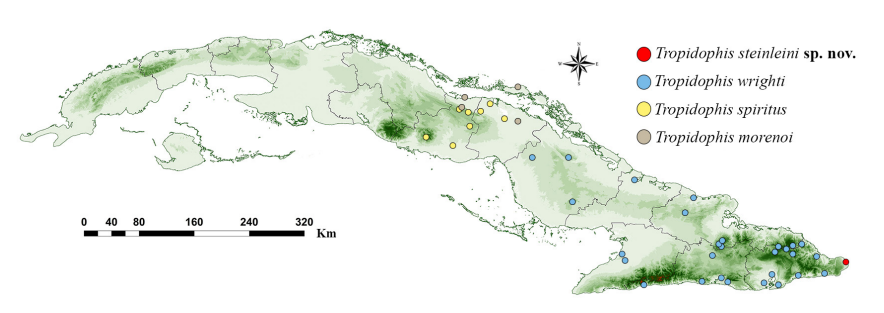

Distribution (Fig. 4). Only known from the type locality, at sea level, in the subcoastal semidesert area of Maisí, Guantánamo, eastern Cuba.

Figure 4. Distribution of Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov., and related species T. wrighti, T. spiritus and T. morenoi. Plotted localities follow records by Domínguez and Parada (2009), Fong and Armas (2011), Rodríguez-Schettino et al. (2013), authors’ observations, and specimens listed in Appendix 1.

Ecological notes. The habitat of Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov. is one of the driest areas in Cuba (Fig. 5). The only known female was associated with xeric vegetation formed by low dry scrub and cacti, in the coastal semi-desertic surroundings of the lighthouse at Punta Maisí. The individual was found on the cemented border of a well, probably in search of water. Efforts to locate more individuals in the wild were unsuccessful and no other specimens have been located in any Cuban institution, which may indicate that the species is rare and/or difficult to find. The overall morphology of the new species suggests it is semi-arboreal and probably preys mainly on sleeping anole lizards, like other species with similar habitus.

Figure 5. Habitat of Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov. in the surroundings of the lighthouse at Maisí, Guantánamo Province, eastern Cuba. This is one of the driest regions of the island. Photo: L. M. Díaz.

DISCUSSION

Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov is similar to other snakes of the genus in that it is relatively rare and difficult to collect. For this reason, many Tropidophis are often described from a single specimen (e.g., T. celiae, T. hendersoni, and T. spiritus); however, species that were first described only from their holotype (Hedges et al., 1999; Hedges & Garrido, 1999, 2002) were later validated by additional material, probably stimulated by their original description (e.g., Fong & Armas, 2011; Díaz et al., 2014; Torres et al., 2013a, 2018). Given the unpredictable nature of the occurrence of Tropidophis in the wild, we considered that the combination of an exclusive morphology, color pattern, and genetic distinction provided sufficient evidence to support the recognition of a distinct species, despite the fact that it was based on only one specimen available.

Our molecular tree (Fig. 3) agrees in most respects with the general classification given by Hedges (2002: 84), who also recognized three species groups of Cuban Tropidophis: pardalis, melanurus, and maculatus (Figs. 6–8). The classification of most species largely agrees with this author’s scheme but some of them, for which he lacked genetic information, have different phylogenetic relationships than previously thought. This supports Hedges’ own statement that external morphology does not always reflect the most immediate relationships between species.

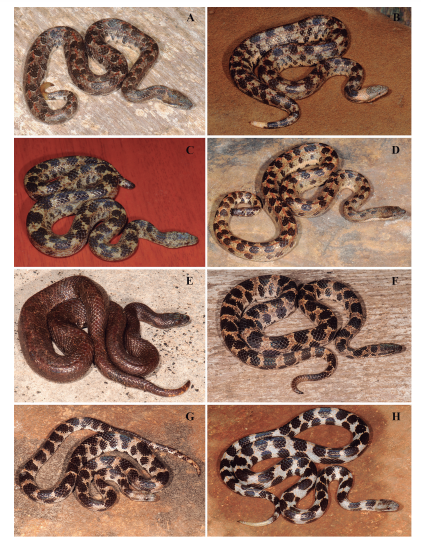

The T. pardalis species group is the largest clade (Fig. 3) and includes the species

T. fuscus, T. morenoi, T. pardalis, T. pilsbryi, T. spiritus, Tropidophis steinleini sp. nov., T. wrighti, and T. xanthogaster (Fig. 6). Hedges (2002) also included T. nigriventris in this group, but because it is the only species omitted in our phylogeny, we cannot re-evaluate its relationships. T. nigriventris and T. hardyi are very similar to T. pardalis and deserves a new integrative taxonomic review in order to understand species boundaries and phylogeography. The specimen herein assigned to T. hardyi based on morphological characters, is very narrowly distant to T. pardalis. T. fuscus + T. pilsbryi are sister species to all the other species of this clade. T. steinleini sp. nov. is basal to the species radiation contained in two subclades: T. morenoi + T. spiritus + T. wrighti and T. hardyi + T. pardalis + T. xanthogaster. Species in this clade have either small to medium-sized blotches (most species) or large blotches along the body (T. morenoi, T. spiritus, T. steinleini sp. nov. and T. wrighti) arranged in 4 to 10 rows, depending on species. Body form varies from stocky (T. hardyi, T. nigriventris, T. pardalis, T. pilsbryi and T. xanthogaster) to distinctively slender, very likely according to their foraging behaviors. Only Cuban species have been previously considered within the T. pardalis species group (Hedges, 2002).

Tropidophis morenoi was formerly placed in the T. maculatus species group by Hedges (2002) based on its high number of ventral scales, but counts overlap with T. spiritus. Tropidophis spiritus (Fig. 6F) may variably have blotches transversally fused, like T. morenoi (Fig. 6G), giving them a banded appearance. “Typical” and “banded” individuals are known to occur at Jobo Rosado (Sancti Spiritus), but it is unclear whether the two species coexist or if observed patterns are part of one species variation. The banded pattern was mentioned as one of the diagnostic characters of T. morenoi by Hedges et al. (2001) but its presence in neonates of T. spiritus and also in some adults (LMD, pers. obs.) gives rise to some confusion. We found a low genetic distinction among single individuals of T. morenoi and T. spiritus. Better sampling is necessary to confirm the validity of T. morenoi, but very likely it is a synonym of T. spiritus based on the lack of diagnostic characters.

There is a controversial mainland species that deserves special attention and further research. Curcio et al. (2012) discussed the distinctive traits of T. battersbyi compared to other South American species, particularly its unique color pattern, pholidosis and the presence of 12 maxillary teeth (versus the range of 15–20 in T. grapiuna, T. paucisquamis, T. preciosus, and T. taczanowskyi). Hedges (2002) considered T. battersbyi part of the T. taczanowskyi species group despite its very divergent characteristics. T. battersbyi was described by Laurent (1949) from “Ecuador” based on one male specimen at L’Institute Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique (IRSNB 2050), however, the description lacked information about exact locality (see detailed photographs of specimen in Curcio et al., 2012). The specimen information provided by Laurent suggest that it was part of the amphibians and reptiles supposedly collected in the Andes of Ecuador by Émile de Ville, and received in 1874-1875 by The Royal Museum of Natural History in Brussels (see Boulenger, 1880), more exactly November 20, 1875 (according to Wallach et al., 2014: 752); however, É. de Ville died in 1853, so this date must be inaccurate. T. battersbyi has not been found in South America since it was first named. Laurent (1949) described that T. battersbyi was more similar to the Cuban species T. wrighti from which it differed by having smooth scales versus the keeled scales of the latter. Laurent declared that, despite the geographical distance, T. battersbyi appears to be a simple variation of T. wrighti. However, T. wrighti mostly has smooth scales, except for the dorsalmost rows that can be weakly keeled according to Schwartz and Henderson (1991). T. battersbyi is not only similar to T. wrighti in overall appearance, but it is also similar to T. spiritus and T. morenoi in that it has six rows of large blotches around the body (versus typically four in T. wrighti), some of them transversally fused, 200 ventral scales, 41 subcaudal scales, dorsal scales 21–23–17, interparietal scales present, dark parietal spots (faded but defined in the T. battersbyi specimen), and a postocular stripe. It cannot be ruled out that the only known specimen of T. battersbyi was assigned to an incorrect locality, as very often happens with some old specimens which traveled from the New World to Europe, and that its provenance was very likely to be Cuba. The history of this specimen remains a mystery but, in any case, it is obvious that T. battersbyi may actually represent a former synonym of either of the most recently described species related to T. wrighti: T. spiritus and T. morenoi. The taxonomy of these species needs to be revisited, as previously mentioned. A very similar case occurred with T. moreletii. It was described by Bocourt (1885) who stated that the type specimen was collected by A. Morelet in Vera-Paz, Guatemala. Stejneger (1917) corrected the issue, and synonymized T. moreletii with T. semicinctus since Arthur Morelet was collecting in Cuba for two months before he continued to Guatemala. Stull (1928) mentioned this example and others, suggesting that geographic mislabeling was frequent in old specimens of Tropidophis.

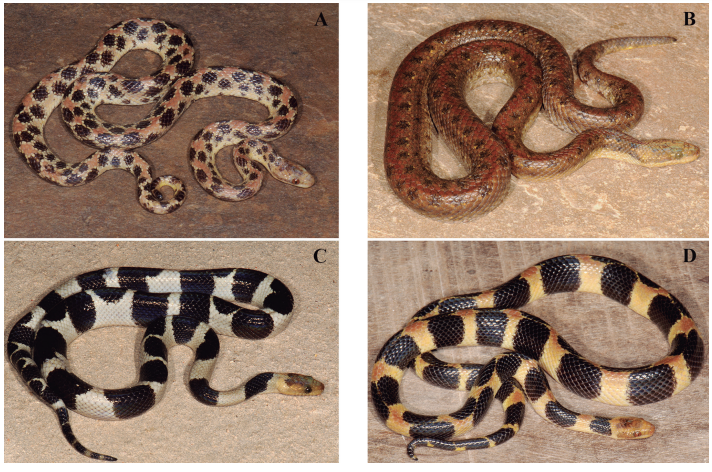

The T. melanurus species group comprises three Cuban species: T. celiae, T. hendersoni and T. melanurus (Fig. 7). Previously, T. hendersoni was considered by Hedges (2002) to belong to the T. pardalis species group. Torres et al. (2017, 2018) compared the morphology of T. celiae and T. hendersoni (Fig. 7 A, B) and assumed a close relationship among them. Our phylogeny shows that T. hendersoni is the sister species of T. melanurus + T. celiae. Outside the Cuban archipelago the following species have been considered to belong to this clade (Hedges, 2002): T. canus (Bahamas), T. curtus (Bahamas), T. caymanensis (Grand Cayman), T. parkeri (Little Cayman), T. schwartzi (Cayman Brac), and T. bucculentus (Navassa Island). Species in this group are mainly terrestrial but some occasionally climb on thick branches and trees such as Ficus. T. melanurus is the largest species of the genus [one record over 1220 mm in total length (Alayo, 1951); 1100 mm, L. M. D. (personal observation)], with keeled scales. All species in this group have two slightly enlarged paravertebral rows of blotches that contrast with the much smaller lateral ones. However, heavily spotted, striped, or plain-colored individuals are present in many populations of T. melanurus at different frequencies of occurrence. The status of western and eastern populations has to be evaluated in the future since T. melanurus might be paraphyletic and closely-related species exist outside the Cuban territory.

Figure 6. Cuban snakes of the Tropidophis pardalis species group. A, T. pardalis, female, from Boyeros, La Habana Province; B, T. pardalis, female, from Soroa, Candelaria, Artemisa Province; C, T. xanthogaster, male, from La Bajada, Guanahacabibes, Pinar del Río Province; D, T. hardyi, male, from Río Jutía, Guajimico, Cienfuegos Province; E, T. fuscus, female, from Altiplanicie de El Toldo, Humboldt National Park, Holguín province; F, T. spiritus, female, from Alturas de Banao, Sancti Spiritus Province; G, T. cf. morenoi, male, from Jobo Rosado, Villa Clara Province; H, T. wrighti, from Altiplanicie de El Toldo, Humboldt National Park, Holguín Province. Photos: L. M. Díaz.

Figure 7. Cuban snakes of the Tropidophis melanurus species group. A, T. celiae, female from Carboneras, Matanzas Province; B, T. hendersoni, male, from Cueva de los Panaderos, Gibara, Holguín Province; C, T. melanurus melanurus, female, from Boyeros, La Habana Province; D, T. m. ericksoni, male, from Los Indios, Isla de la Juventud. Photos: L. M. Díaz.

Figure 8. Cuban snakes of the Tropidophis maculatus species group. A, T. maculatus, male, fom Boca de Jaruco, Mayabeque Province; B, T. galacelidus, female, from Codina, Topes de Collantes, Cienfuegos Province; C, T. feicki, female, from Moncada, Viñales, Pinar del Río Province; D, T. semicinctus, female, from El Cubano, Trinidad, Sancti Spiritus Province. Photos: L. M. Díaz.

The T. maculatus species group includes T. feicki, T. galacelidus, T. maculatus, and T. semicinctus (Fig. 8). T. galacelidus was formerly named (Schwartz & Garrido, 1975) as a subspecies of T. pilsbryi, until it was raised to the specific level by Hedges and Garrido (2002) who tentatively placed it in the T. pardalis group (Hedges, 2002). Our new classification corroborates the specific status of T. galacelidus because T. pilsbryi is more closely related to T. fuscus in the T. pardalis clade. Only Cuban species have been previously considered to belong to this group. Species in this group tend to be slender and good climbers. The most stocky species is T. galacelidus. Except for the latter, the species in that group are characterized by having the largest eyes in proportion to the head among all Cuban species, a narrow neck, and a laterally compressed body, which are all indicative features of extreme arboreality (see also Hedges & Garrido, 1992). Only the large-spotted species in the T. pardalis group are somewhat convergent with species in this clade. T. feicki was recovered as the sister species of the other three taxa in this group. No species in this group has been found in the easternmost part of Cuba. T. galacelidus is the sister species of T. maculatus + T. semicinctus. Based on these phylogenetic results, it is evident that the pattern of large blotches of T. feicki and T. semicinctus (fused in bands or typically in two rows, respectively) versus the small blotches arranged in multiple rows of T. galacelidus and T. maculatus, have evolved at least twice within the group.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Alexander Arango, Javier Torres, Dariel López and Diego Salas for granting access to live specimens of Tropidophis; Ansel Fong (BIOECO) and Manuel Iturriaga (IES), David Kizirian, Christopher Raxworthy (AMNH), José Rosado (MCZ), Michel Sánchez, Kevin de Queiroz and James Poindexter II (USNM) for allowing the examination of specimens under their care. To Ariatna Linares always for her logistic support, and to Hiroshi D. Akashi, Gerardo Begué, Ángel Céspedes, Jordi Giralt, Manuel Iturriaga, Yamilka Joubert, Masakado Kawata, Arian Linares, Dariel López, José L. Ponce, Gerardo Revilla, Leodan Roque, Yonder Verdecia, and personnel of the Humboldt National Park for their assistance and companionship during field work. Also, our gratitude to Reinaldo Estrada for providing us the map we used to plot species distribution. Kraig Adler, Lynn Dunlap, Esteban Gutiérrez, Masakado Kawata, Jeff Lemm, Carlos Suriel and Hussam Zaher, provided valuable comments on manuscript. Yasel Alfonso kindly shared literature. This work is part of the project “Taxonomía de algunos grupos zoológicos de Cuba y del Caribe, con acciones de capacitación especializada, divulgación, y educación ambiental” coordinated by LMD at the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Cuba. Field work was supported by grants from WWF, the Linnean Society of London, the Mohamed Bin Zayed Foundation, and Wolfgang Feichtinger, Claus Steinlein and Michael Schmid (University of Würzburg, Germany).

Literatura Citada

Adalsteinsson, S. A., W. R. Branch, S. Trape, L. J. Vitt, & S. B. Hedges. 2009. Molecular phylogeny, classification, and biogeography of snakes of the Family Leptotyphlopidae (Reptilia, Squamata). Zootaxa, 2244: 1–50.

Alayo, P. 1951. Especies herpetológicas halladas en Santiago de Cuba. Boletín de Historia Natural de la Sociedad “Felipe Poey”, 2: 106–110.

Armas, L. F. de, & M. Iturriaga. 2017. Depredación de Hemidactylus mabouia (Squamata: Gekkonidae) por Tropidophis pardalis (Serpentes: Tropidophiidae). Novitates Caribaea, 11: 99–102.

Bailey, J. R. 1937. A review of some recent Tropidophis material. Proceedings of the New England Zoological Club, 16: 41–52.

Bocourt, M. F. 1885. Note sur un Boidien nouveau, provenant du Guatémala. Bulletin de la Société Philomathique de Paris, 7 (9): 113–115.

Boulenger, G. A. 1880. Reptiles et batraciens recueillis par M. Emile de Ville dans les Andes de l’Equateur. Bulletin de la Société Zoologique de France, 5: 41–48.

Cajigas G., A., J. Torres L., & O. J. Torres F. 2018. Tropidophis maculatus (Spotted Red Trope). Geographic Distribution. Herpetological Review, 49 (1): 80–84.

Cocteau, J. T., & G. Bibron. 1843. Reptiles, pp. 1–142. In: Sagra, R. de la, Historia Física, Política y Natural de la Isla de Cuba. Tomo IV. Reptiles y Peces. Segunda parte, Historia Natural. Paris: Bertrand, 255 pp. + Plates I-V.

Curcio, F. F., P. M. Sales Nunes, A. J. Suzard Argolo, G. Skuk, & M. Trefaut Rodrígues. 2012. Taxonomy of the South American dwarf boas of the genus Tropidophis Bibron, 1840, with the description of two new species from the Atlantic forest (Serpentes: Tropidophiidae). Herpetological Monographs, 2012 (26): 80–121.

Díaz, L. M., A. Cádiz, S. Villar, & F. Bermúdez. 2014. Notes on the ecology and morphology of the Cuban khaki trope, Tropidophis hendersoni Hedges and Garrido (Squamata: Tropidophiidae), with a new locality record. IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians, 21: 116–119.

Domínguez, M., & L.V. Moreno. 2005. Tropidophis pilsbryi (NCN). Size record. Herpetological Review, 37 (3): 330.

Domínguez, M., & L.V. Moreno. 2006a. Tropidophis morenoi (NCN). Size record. Herpetological Review, 37 (3): 356.

Domínguez, M., & L.V. Moreno. 2006b. Tropidophis pardalis (NCN). Size record. Herpetological Review, 37 (3): 356.

Domínguez, M., & L.V. Moreno. 2006c. Tropidophis maculatus (NCN). Size record. Herpetological Review, 37 (3): 355–356.

Domínguez, M., & A. Parada. 2009. Tropidophis morenoi (NCN), Cuba. Geographic distribution. Herpetological Review, 40 (4): 458.

Domínguez, M., L. V. Moreno, & S. B. Hedges. 2006. A new snake of the genus Tropidophis (Tropidophiidae) from the Guanahacabibes Peninsula of Western Cuba. Amphibia-Reptilia, 27: 427–432.

Domínguez, M., L.V. Moreno, & M. Sánchez. 2005. Tropidophis wrighti (NCN). Size record. Herpetological Review, 36 (2): 197.

Figueroa, A., A. D. McKelvy, L. L. Grismer, C. D. Bell, & S. P. Lailvaux. 2016. A species-level phylogeny of extant snakes with description of a new colubrid subfamily and genus. PLoS ONE, 11 (9): e0161070, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161070.

Fong G., A. 2002. Tropidophis fuscus. Geographic distribution. Herpetological Review, 33 (4): 326.

Fong G., A., & L. F. de Armas. 2011. The easternmost record for Tropidophis spiritus Hedges and Garrido, 1999 (Serpentes: Tropidophiidae) in Cuba. Herpetology Notes, 4: 111–112.

Fong G., A., I. Bignotte Giró, & K. Maure García. 2013. Unsuccessful predation on the toad Peltophryne peltocephala (Bufonidae) by the Cuban snake Tropidophis melanurus (Tropidophiidae). Herpetology Notes, 6: 73–75.

García-Padrón, L. Y., J. Torres & M. Boligan Expósito. 2020. Aberrant body markings in the Cuban banded dwarf boa, Tropidophis feicki (Squamata: Tropidophiidae). The Herpetological Bulletin, 152: 38–39.

González, H., L. Rodríguez-Schettino, A. Rodríguez, C. A. Mancina, & I. Ramos García. 2012. Libro Rojo de los vertebrados de Cuba. Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, Edición Academia, 304 pp.

Gundlach, J. C. 1840. Ueber zwei von mir gesammelte Boen von Cuba. Archiv für Naturgeschichte von Wiegmann, 6 (1): 359–361.

Hedges, S. B. 2002. Morphological variation and the definition of species in the snake genus Tropidophis (Serpentes, Tropidophiidae). Bulletin of the Natural History Museum [London], Zoology Series, 68: 83–90.

Hedges, S. B., & O. H. Garrido. 1992. A new species of Tropidophis from Cuba (Serpentes: Tropidophiidae). Copeia, 3: 820–825.

Hedges, S. B., & O. H. Garrido. 1999. A new snake of the genus Tropidophis (Tropidophiidae) from central Cuba. Journal of Herpetology, 33 (3): 436–441.

Hedges, S. B., & O. H. Garrido. 2002. A new snake of the genus Tropidophis (Tropidophiidae) from eastern Cuba. Journal of Herpetology, 36 (2): 157–161.

Hedges, S. B., A. R. Estrada, & L. M. Díaz. 1999. New snake (Tropidophis) from Western Cuba. Copeia, 1999 (2): 376–381.

Hedges, S. B., O. H. Garrido, & L. M. Díaz. 2001. A new banded snake of the genus Tropidophis (Tropidophiidae) from north-central Cuba. Journal of Herpetology, 35 (4): 615–617.

Henderson, R. W., & R. Powell. 2009. Natural History of West Indian Reptiles and Amphibians. Univ. Press Florida, Gainesville, xxiv + 496 pp.

Hoser, R. T. 2013. A reassessment of the Tropidophiidae, including the creation of two new tribes and the division of Tropidophis Bibron, 1840 into six genera, and a revisiting of the Ungaliophiinae to create two subspecies within Ungaliophis panamensis Schmidt, 1933. Australasian Journal of Herpetology, 17: 22–34.

Iturriaga, M. 2014. Autohemorrhaging behavior in the Cuban Dwarf Boa Tropidophis melanurus Schlegel, 1837 (Serpentes: Tropidophiidae). Herpetology Notes, 7: 339–341.

Iturriaga, M., & M. A. Olcha. 2015. Geographic Distribution: Tropidophis fuscus. Herpetological Review, 46 (3): 387.

Jobb, G., A. von Haeseler, & K. Strimmer. 2004. TREEFINDER: a powerful graphical analysis environment for molecular phylogenetics. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 4: 18.

Kaiser, H., B. I. Crother, C. M. R. Kelly, L. Luiselli, M. O’Shea, H. Ota, P. Passos, W. D. Schleip, & W. Wüster. 2013. Best practices: In the 21st century, taxonomic decisions in herpetology are acceptable only when supported by a body of evidence and published via peer-review. Herpetological Review, 44 (1): 8–23.

Köhler, G. 2012. Color catalogue for field biologists. Herpeton, Offenbach, Germany, 49 pp.

Laurent, R. 1949. Notes sur quelq ues reptiles appartenant a la collection de L’Institute Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique. III. Formes ame´ ricaines. Bulletin de L’Institute Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, 25: 1–20.

Polo, J. L., & A. Arango. 2011. Mantenimiento y reproducción del majasito o boa leopardo Tropidophis pardalis Gundlach, 1840 (Serpentes: Tropidophiidae) en el Parque Zoológico Nacional de Cuba. CubaZOO, 24: 45–52.

Pook, C. E., W. Wüster, & R. S. Thorpe. 2000. Historical biogeography of the western rattlesnake (Serpentes: Viperidae: Crotalus viridis), inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence information. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 15 (2): 269–282.

Posada, D., & K. A. Crandall. 1998. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics Applications Note, 14 (9): 817–818.

Rehak, I. 1987. Color change in the snake Tropidophis feicki (Reptilia: Squamata: Tropidophiidae). Vestník Ceskoslovenské spolecnosti zoologické, 51: 300–303.

Reynolds, R. G., M.L. Niemiller, & L. J. Revell. 2014. Toward a Tree-of-Life for the boas and pythons: Multilocus species-level phylogeny with unprecedented taxon sampling. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 71 (2014): 201–213.

Reynolds, R. G., A. R. Puente-Rolón, A. L. Castle, M. Van De Schoot, & A. J. Geneva. 2018. Herpetofauna of Cay Sal, Bahamas and phylogenetic relationships of Anolis fairchildi, Anolis sagrei, and Tropidophis curtus from the region. Breviora, 560: 1–19, doi: 10.3099/ MCZ45.1.

Rhodin, A. G. J., H. Kaiser, P. P. van Dijk, W. Wüster, M. O’Shea, M. Archer, M. Auliya, L. Boitani, R. Bour, V. Clausnitzer, T. Contreras-MacBeath, B. I. Crother, J. M. Daza, et al. 2015. Comment on Spracklandus Hoser, 2009 (Reptilia, Serpentes, Elapidae): request for confirmation of the availability of the generic name and for the nomenclatural validation of the journal in which it was published. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 72 (1): 61–78.

Rodríguez-Cabrera, T. M., L. Y. García-Padrón, & J. Torres. 2020a. New dietary records for the Cuban Spotted Red Trope, Tropidophis maculatus (Squamata: Tropidophiidae). Caribbean Herpetology, 73: 1–2.

Rodríguez-Cabrera, T. M., J. Torres & E. Morell Savall. 2020b. Easternmost record of the Cuban Broad-banded Trope, Tropidophis feicki (Squamata: Tropidophiidae), of Cuba. Caribbean Herpetology, 71: 1–3.

Rodríguez-Cabrera, T. M., J. Rosado, R. Marrero, & J. Torres. 2017. Birds in the diet of snakes in the genus Tropidophis (Tropidophiidae): do prey items in museum specimens always reflect reliable data? IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians, 24 (1): 61–64.

Rodríguez-Schettino, L., C. A. Mancina, & V. Rivalta González. 2013. Reptiles of Cuba: checklist and geographic distributions. Smithsonian Herpetological Information Service, 144: 1–98.

Rodríguez-Schettino, L., V. Rivalta González, A. González R., & R. Fernández de Arcila F. 2015. Presencia del género Tropidophis (Serpentes: Tropidophiidae) en el Sistema Nacional de Áreas Protegidas de Cuba. Revista Colombiana de Ciencia Animal, 7: 19–24.

Schlegel, H. 1837. Essai sur la physionomie des serpens. Partie Descriptive. La Haye (J. Kips, J. H Z. et W. P. van Stockum), 606 S. + xvi.

Schwartz, A. 1957. A new species of boa (genus Tropidophis) from western Cuba. American Museum Novitates,1839: 1–8.

Schwartz, A., & O. H. Garrido. 1975. A reconsideration of some Cuban Tropidophis

(Serpentes, Boidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 88 (9): 77–90.

Schwartz, A., & R. J. Marsh. 1960. A review of the pardalis-maculatus complex of the boid genus Tropidophis of the West Indies. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 123 (2): 49–84.

Schwartz, A., & R. Thomas. 1960. Four new snakes (Tropidophis, Dromicus, Alsophis) from the Isla de Pinos and Cuba. Herpetologica, 16 (2): 73–90.

Schwartz, A., & R. W. Henderson. 1991. Amphibians and Reptiles of the West Indies. Descriptions, distributions, and natural history. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, xvi + 720 pp.

Stejneger, L. H. 1917. Cuban amphibians and reptiles collected for the United States National Museum from 1899 to 1902. Proceedings of the US Natl. Mus., 53: 259–291.

Stull, O. G. 1928. A revision of the genus Tropidophis. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, Univiversity of Michigan, 195, 1–49 + 3 figs.

Tolson, P. J., & R. W. Henderson. 1993. The Natural History of West Indian Boas. R&A Publishing Ltd., Taunton, Somerset, England, 125 pp.

Torres, J., & C. A. Martínez-Muñoz. 2014. Tropidophis maculatus. Maximum size. Natural History Notes. Herpetological Review, 45 (2): 345.

Torres. J. & T. M. Rodríguez-Cabrera. 2020. Diurnal refuge sharing between species of Cuban snakes of the genus Tropidophis (Squamata: Tropidophiidae). Caribbean Herpetology, 74: 1–2.

Torres, J., C. Pérez-Penichet, & O. Torres. 2014. Predation attempt by Tropidophis melanurus (Serpentes, Tropidophiidae) on Anolis porcus (Sauria, Dactyloidae). Herpetology Notes, 7: 527–529.

Torres, J., R. Powell, & A. R. Estrada. 2018. Tropidophis celiae. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles, 914: 1–8 pp.

Torres, J., R. Powell, & O. H. Garrido. 2017. Tropidophis hendersoni. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles, 907: 1–8 pp.

Torres, J., O. J. Torres, & R. Marrero. 2013a. Autohemorrage in Tropidophis xanthogaster (Serpentes: Tropidophiidae) from Guanahacabibes, Cuba. Herpetology Notes, 6: 579–581.

Torres, J., O. J. Torres, & R. Marrero. 2013b. Nueva localidad para la boa enana Tropidophis celiae Hedges, Estrada y Díaz, 1999 (Serpentes, Tropidophiidae) en Cuba. Revista Cubana de Ciencias Biológicas, 2: 79–82.

Torres, J., T. M. Rodríguez-Cabrera, R. Marrero Romero, O. J. Torres Fundora, & P. Gutiérrez Macías. 2016. Comments on the critically endangered Canasí Trope (Tropidophis celiae, Tropidophiidae): neonates, ex situ maintenance, and conservation. IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians, 23 (2): 82–87.

Uetz, P., P. Freed & J. Hošek (Eds). 2020. The Reptile Database. Available: http://www.reptiledatabase.org , (accessed: may 9, 2020).

Wallach, V., K. L. Williams, & J. Boundy. 2014. Snakes of the World: a catalogue of living and extinct species. Taylor and Francis, CRC Press, 1237 pp.

Wilcox, T. M., D. J. Zwickl, T. A. Heath, & D. M. Hillis. 2002. Phylogenetic relationships of the dwarf boas and a comparison of Bayesian and bootstrap measures of phylogenetic support. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 25: 361–371.

APPENDIX 1

SPECIMENS EXAMINED FOR COMPARISONS AND GENETIC PHYLOGENY

Tropidophis celiae (n = 2).— MNHNCu 4474 (holotype), Alturas de Canasí, Santa Cruz del Norte, La Habana Province; CZACC 4.5582, Carboneras, Cárdenas, Matanzas.

Tropidophis galacelidus (n = 6).— MNHNCu 4523, Pico Potrerillo, Topes de Collantes,

Macizo de Guamuhaya, Sancti Spiritus Province; CZACC 4.4301, Topes de Collantes, Sancti Spiritus; CZACC 4.5744, 4.5601, 4.5602, Sierra de Banao, Sancti Spiritus; CZACC 4.5748, Sierra de Trinidad, Sancti Spiritus.

Tropidophis feicki (n = 4).— MNHNCu 4999–5000, Moncada, Viñales, Pinar del Río Province; MNHNCu 5111, San Vicente, Viñales; CZACC 4.11246, Sierra de San Carlos, Pinar del Río.

Tropidophis fuscus (n = 9).— Holguín: MNHNCu 4340, Alto de la Calinga, Moa, Holguín Province; BSC.H 751, 752, 753, and 2026, Altiplanicie de El Toldo, Parque Nacional

A. de Humboldt, Holguín; MNHNCu 2705 (holotype), Minas Amores, 21.7 km NW and

7.7 km SE of Baracoa, Guantánamo Province; MNHNCu 4826–27, Altiplanicie de El Toldo, Parque Nacional

A. de Humboldt, Holguín; MNHNCu 4828, Idem.

Tropidophis hardyi (n = 2).— USNM 138510 (holotype), 16 km W of Trinidad, Sancti Spiritus Province; MNHNCu 5125, Río Jutía, Guajimico, Cienfuegos Province.

Tropidophis hendersoni (n = 6).— MCZ 47896 (holotype), Guardalavaca, Holguín Province. MNHNCu 5055–59, Gibara, Holguín.

Tropidophis maculatus (n = 14).— MNHNCu 3422, Soroa, Candelaria, Artemisa Province; MNHNCu 5001–5002, 5003–5004, Boca de Jaruco, Santa Cruz del Norte, Mayabeque Province; MNHNCu 5089, El Taburete, Sierra del Rosario, Artemisa Province; MNHNCu 5105, Bosque de La Habana, Marianao, La Habana; MNHNCu 5108, Soroa, Candelaria, Artemisa; CZACC 4.5481, Víbora, 10 de octubre, La Habana Province; CZACC 4.5448, Reparto Miraflores, Viejo Boyeros, La Habana; CZACC 5469–70, La Tropical, Bosque de La Habana, Marianao; CZACC 4.5739, Cinco Pasos, San Cristóbal, Artemisa; CZACC 11913, Capdevila, Boyeros, La Habana.

Tropidophis melanurus (n = 7).— MNHNCu 622, Loma El Mulo, Sierra del Rosario, Artemisa province. MNHNCu 594, Santa María del Rosario, Cotorro, La Habana; MNHNCu 342, Vereón, Cabo Cruz, Granma Province; MNHNCu 5085, Lawton, La Habana Province; CZACC 5106, Boyeros, La Habana; MNHNCu 5107, Atarés, Habana Vieja, La Habana; MNHNCu 5117, Soroa, Candelaria, Artemisa Province.

Tropidophis morenoi (n = 3).— IB 2943 (holotype) and IB 2942 (paratype), surroundings of Cueva Humboldt, Caguanes, Villa Clara Province; MNHNCu 5088 Jobo Rosado, Jatibonico, Sancti Spiritus Province.

Tropidophis nigriventris (n = 3).— UMMZ 70888 (holotype; examined from photographs), 6 mi E Martí, Camagüey Province; AMNH 81182–83 (paratypes), “Loma de la Yagua” (comment: probably Yegua or Las Yeguas), El Porvenir, 24 km SW of Camagüey, Camagüey Province.

Tropidophis pardalis (n = 15).— CZACC 4.9132, Santos Suárez, La Habana Province; CZACC 4.4192, Bolondrón, Guanahacabibes, Pinar del Río Province; CZACC 4.10081, Trinidad, Sancti Spiritus; MNHNCu 3614, Santa Lucía, Mantua, 4 km del poblado Río del Medio, Pinar del Río; MNHNCu 502, Pons, Sierra de los Órganos, Pinar del Río Province; MNHNCu 4359, Río Ariguanabo, San Antonio de los Baños, Artemisa Province; MNHNCu 001, Ciudad Libertad, Marianao, La Habana; MNHNCu 4453, Charco del Negrito, San Antonio de los Baños, Artemisa; MNHNCu 588, San Miguel del Padrón, La Habana; MNHNCu 2305,

Santo Tomás, Ciénaga de Zapata, Matanzas Province; MNHNCu 5102, Bosque de La Habana, La Habana Province; MNHNCu 5103–5104, Bosque de La Habana, La Habana Province; MNHNCu 5083, Reparto Bahía, Habana del Este, La Habana; MNHNCu

5109–5110, Soroa, Candelaria, Artemisa Province.

Tropidophis pilsbryi (n = 1).— CZACC 4.5624, El Salvador, Guantánamo (as T. fuscus by Iturriaga & Olcha, 2015).

Tropidophis semicinctus (n = 9).— MNHNCu 4468, Alturas de Canasí, Santa Cuz del Norte, Mayabeque Province; MNHNCu 4831, Bermejas, Zapata, Matanzas Province; MNHNCu 4994, 4995, 4996, 4998, Parque El Cubano, Trinidad, Sancti Spiritus Province; MNHNCu 5080–5082, Cuevas de Saturno, Varadero, Matanzas.

Tropidophis spiritus (n = 5).— MNHNCu 4085 (Holotype), Canal Zaza, Chorrera Brava, Sancti Spiritus Province; CZACC 4.5660, Reserva Ecológica Caja de Agua, Sierra de Banao, Macizo de Guamuhaya, Sancti Spiritus; CMST 189–190, Crucero Tamarindo, Chambas, Ciego de Ávila Province; BSC.H 3573, Loma del Heliógrafo, S of Arroyo Blanco, Sancti Spiritus.

Tropidophis wrighti (n = 12).— CZACC 4.5729, Blanquizal, Manzanillo, Granma Province; CZACC 4.10036, Loma de la Mensura, Pinares de Mayarí, Holguín Province; CZACC 4.10037, 5 km S of Loma de la Mensura, Pinares de Mayarí; CZACC 4.11293, Mayarí, Holguín; CZACC 4.9479–80, Meseta Pinares de Mayarí, Holguín; MNHNCu 4524, Piedra La Vela, Ojito de Agua, Parque Nacional A. de Humboldt, Guantánamo Province; MNHNCu 4829, Altiplanicie de El Toldo, Parque Nacional A. de Humboldt, Holguín Province; MNHNCu 5113–14, Gibara, Holguín; CZACC 4.5482, Loma de Malones, Caimanera, Guantánamo; CZACC 11208, Puerto Manatí, Las Tunas Province.

Tropidophis xanthogaster (n = 5).— MNHNCu 5087, 5124, La Bajada, Guanahacabibes, Pinar del Río Province; CZACC 4.4191, Sandino, Guanahacabibes, Pinar del Río Province; CZACC 4.11922, Bolondrón, Guanahacabibes, P. del Río; CZACC 11584, Cueva de la Escalera, Guanahacabibes, Pinar del Río Province.